I hadn’t been following the news much regarding SQL Server 2016, so when I did some reading the other day I was quite pleasantly surprised by some of the new features announced (not to mention that it looks like SSMS will finally be getting some much needed love). 🙂

We’ve been having some frustrating intermittent performance issues recently, and I was struggling to gain much insight into what the issue was (since we’re using Azure Databases, so scope for troubleshooting is a little narrower than for on-premise SQL servers). So when I read about the “Query Store” feature available in SQL Server 2016 and Azure Database (v12) I got quite excited.

What is it?

I’ll keep this short and sweet since there’s already a few good posts out there about the Query Store. Basically this feature allows you to track down queries which have “regressed” (i.e. it was performing well, and then all of a sudden it turned to crap for no apparent reason).

Not only can you track them down, you can now “pin” the old (i.e. good) execution plan. Essentially you’re overriding the optimiser and telling it that you in fact know better.

Sweet! How do I do it?

You could do this before now, by forcing plans using USE PLAN query hints, etc. But the Query Store and it’s related new shiny UI makes it soooo much easier and “trackable”.

As I said before though, I’m not going to go into details about how to use it. I used this post to figure out how it works, how to force plans, how to monitor how it’s going, etc.

Ok, so how did it help?

Our problem was that we were seeing intermittent DTU spikes (remember, we’re on Azure, so this means we were maxing out our premium-tier database’s resources in some way, whether CPU, Disk I/O, etc). We tracked it down to a heavy stored procedure call which was running well 99% of the time, but would get a “bad plan” every now and then. So we would see a spike in our app response time in New Relic, I’d jump into a query window and run an sp_recompile on this proc, and usually the problem would go away (until the next time).

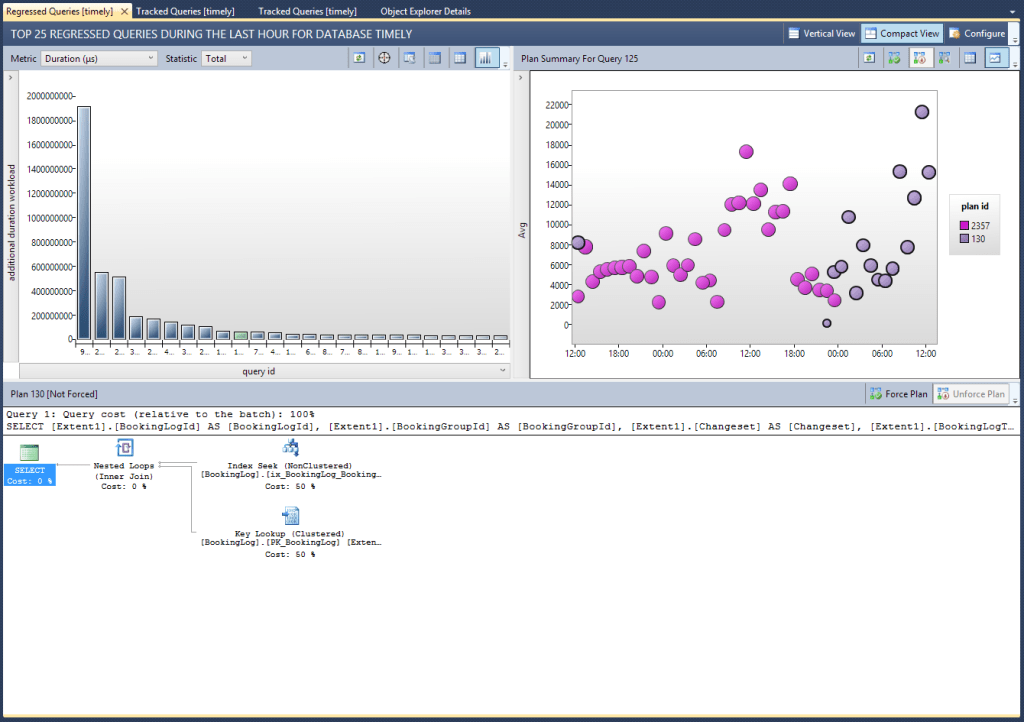

Obviously this wasn’t a sustainable approach, so I needed to either rewrite the proc to make it more stable, tweak some indexes, or force a plan. I fired up the new “Regressed Queries” report (shown above) and it quickly highlighted the problem query. From there it was a case of selecting the “good” plan, and hitting the “Force Plan” button. Well… I don’t trust buttons so I actually ran the TSQL equivalent, sys.sp_query_store_force_plan.

Some interesting observations

In the above image you can see the forced plan (circles with ticks in them). What seems to happen, which initially threw me, is that when you force a plan SQL generates a new plan which matches the forced plan, but is picked up as a different plan by the Query Store. Which is why you see the ticks in the circles up until the point you actually pin the plan, after which point you get a new, un-ticked plan. At first I thought this meant it wasn’t working, but it does indeed seem to stick to this forced plan.

Other uses

I’ve also found the reports very useful even when not resorting to forcing plans. In several cases I’ve found queries which aren’t performing as well as they should be, and either altered the query or some underlying indexes, and then seen the (usually) positive resultant new plans; as shown in the image below, where this query was a bit all over the place until I slightly altered an existing index (added 1 included column) and it has since settled on a better, more stable plan (in purple).

Cheers,

Dave